My horse has a snotty nose, what does it mean?

Dr David Marlin and Dr Kristie Pickles have teamed up to talk about the snotty horse and what conditions of the lower and upper respiratory tract can cause nasal discharge. NB articles contains descriptive images of respiratory conditions.

Dr David Marlin & Dr Kristie Pickles

Equestrian writer, 03/02/2020

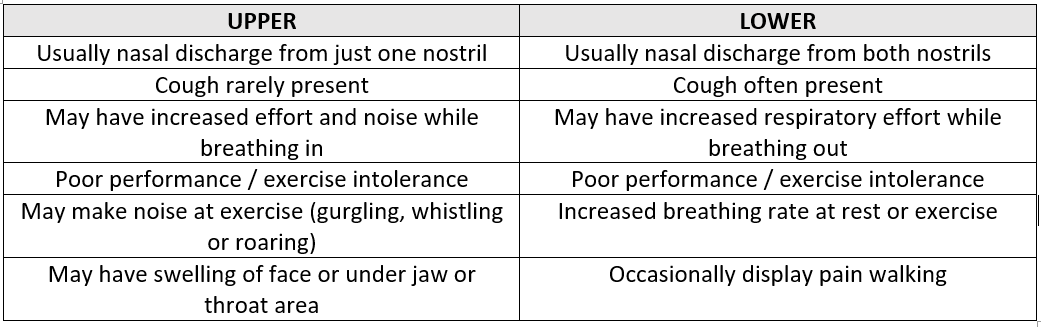

Horses can get a snotty nasal discharge for many reasons. The first challenge is to figure out where the nasal discharge is coming from, as this helps narrow down what may be causing the discharge. Broadly speaking, this can be divided into the upper and lower respiratory tract; the upper respiratory tract encompassing the air conducting passages in the head and throat and the lower respiratory tract being the windpipe (trachea) and lungs. Table 1 gives guidelines for determining if the nasal discharge is coming from the upper or lower respiratory tract. Your vet will be able to confirm the origin of the nasal discharge by performing endoscopy.

Table 1 : Common Characteristics of equine upper and lower respiratory disease.

Upper Respiratory Tract causes of a snotty nose

Sinusitis / Guttural Pouch Disease / Infectious Virus

• Sinusitis

Sinusitis can be divided into primary and secondary sinusitis. Primary sinusitis is caused by viruses, bacteria and occasionally fungi. Secondary sinusitis is caused by a mass within the sinus, e.g. cyst or tumour, or advanced dental disease e.g. infected tooth. Horses generally present with a smelly, purulent nasal discharge and facial swelling above the upper cheek teeth on the side of the diseased sinus, but are otherwise well. Diagnosis is by endoscopy and radiography (x-ray) of the head as well as oral examination. Primary sinusitis is usually treatable with antibiotics alone in the early stages but more chronic disease often requires flushing of the sinus to wash out thick purulent material as drainage from the equine sinuses is very poor. Secondary sinusitis requires the primary disease to be treated.

• Guttural Pouch Disease

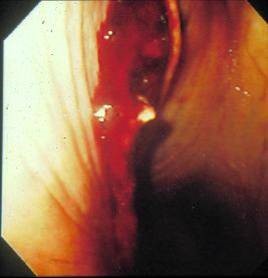

Bacterial infection of the guttural pouch is usually caused by Streptococcus bacteria, the most severe and important manifestation of which is ‘Strangles’ caused by Streptococcus equi var. equi. This is a very contagious infection which rapidly spreads between horses. The disease continually circulates in the horse population due to a small percentage of horses becoming chronic carriers and intermittently shedding bacteria in their nasal secretions despite appearing clinically well. Horses with strangles present with fever, inappetence, swollen lymph nodes in the throat area and a purulent nasal discharge (Fig. 1). Both guttural pouches are usually infected and therefore the nasal discharge is from both nostrils. Diagnosis is via culture and PCR (DNA testing) of throat swabs or guttural pouch washings. Despite being a bacterial infection, strangles is not usually treated with antibiotics as it is believed to increase the risk of horses becoming carriers, which can continue to chronically shed the bacteria responsible, and the formation of abscesses.

• Infectious Viruses

Equine influenza virus, equine rhinovirus, and equine herpesvirus types 1 & 4 can all cause infectious upper respiratory tract disease. These viruses tend to cause a watery or white nasal discharge, fever, inappetence and lethargy. Additionally, a harsh cough is often present with equine influenza. If secondary bacterial infection occurs, the nasal discharge will become purulent. These viruses can also be spread by healthy looking horses with subclinical or inapparent clinical infections. When major changes in the virus structure occur, or if the percentage of vaccinated horses falls below the required quota to provide ‘herd immunity’, major disease outbreaks can occur like the equine influenza outbreak in 2019. These infections can be diagnosed by swabbing of the back of the throat. Treatment is symptomatic (controlling fever with anti-inflammatories) and rest. Appropriate rest is very important to allow the respiratory tract to adequately heal before exercise is resumed otherwise ow grade nonspecific airway disease can persist for many weeks.

Figure 1: Purulent nasal discharge in a horse with strangles.

Figure 2 : Endoscopic image of the back of a horse’s throat showing blood present at the opening of the guttural pouch in a case of guttural pouch mycosis (fungal infection).

Lower Respiratory Tract Causes of a Snotty Nose

Equine Asthma / Pneumonia / Equine Multinodular Pulmonary Fibrosis / Foreign Body / Neoplasia / Parasites

• Equine Asthma Syndrome

Equine asthma syndrome is the name now used for the disease previously called recurrent airway obstruction (RAO) and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). The name equine asthma better reflects the similarity to human asthma and the breadth of clinical signs - from mild (no clinical signs, only apparent on further diagnostic tests) to severe, where clinical signs such as increased respiratory effort, cough and nasal discharge are present at rest. Inflammatory airway disease, a common subclinical disease that causes poor performance, is now referred to as mild equine asthma.

Equine asthma is believed to be caused by an allergy to airborne particles (allergens) in the environment. Typically, clinical signs are linked to the stable environment (and therefore winter) but some horses have clinical signs at pasture which is referred to as ‘summer onset equine asthma’. The horse’s respiratory tract is exposed to a myriad of airborne allergens and dust particles in a stable. Even a completely healthy horse can develop airway inflammation if exposed to a very dusty environment. Most evidence points to fungal spores, present in hay and straw, as being the principle allergens. When a susceptible horse breathes in the allergen, the respiratory system overreacts and the small airways go into spasm and narrow. The airways also become inflamed and produce increased amounts of mucus and inflammatory cells. Once this occurs, the horse’s lungs become hyperreactive to other irritants such as dust, ammonia from urine, and even cold air. However, the disease is reversible and, if the allergen(s) is removed, the airway will return to normal and clinical signs will disappear (‘disease remission’).

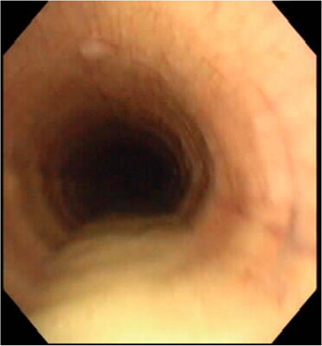

Equine asthma is seen in adult horses, usually greater than 7 years of age. Typical presenting signs include coughing, a white, mucopurulent nasal discharge (Fig. 3) and possibly increased respiratory effort. In severe cases, obvious abdominal effort is visible as the horse breathes out, hence the old name ‘heaves’. Mild asthma with no obvious clinical signs can be seen in younger horses (from 2-3 years of age) and may present only as poor performance. A tentative diagnosis of asthma can usually be made using historical information (such as exposure to dry hay) and clinical signs. Reduction in clinical signs following improvement in the horse’s environment confirms diagnosis. Endoscopy is useful to allow direct visualisation of the windpipe (trachea) and the first part of the lower airway (Fig. 4).

Figure 3 : White nasal discharge from a horse with equine asthma.

Figure 4: Endoscopic picture of a horse’s trachea (windpipe) showing a wide stream of mucopurulent material in a horse with severe equine asthma

The excess mucus and inflammatory cells produced by the lungs can be observed in the lower trachea and a sample collected (via ‘tracheal wash’) for analysis. Respiratory secretions can also be collected from the small airways using a technique called a ‘lung wash’ or ‘bronchoalveolar lavage’. During disease remission these secretions and their cellular content return to normal.

Asthma can be prevented if the causative allergens are known. For example, a horse with allergens in the stable environment can often be kept in remission by avoiding hay and straw. If this isn’t possible and you’re feeding hay or haylage then high temperature steaming is an effective way to reduce airborne respirable dust and allergens prior to feeding. Find out more about high temperature steaming - CLICK HERE. For horses with field-based allergens, this is far harder as the allergens are difficult to determine and are often very hard to avoid. Once diagnosed, the horse will always be susceptible to asthma; the disease is managed not cured. It is best to prevent asthma rather than need to treat it with drugs. If good environmental management cannot be maintained, treatment with oral or inhaled steroids and/or bronchodilators may be required.

• Pneumonia / Pleuropneumonia

Bacterial infection of the lungs (pneumonia) is most commonly seen in foals where Rhodococcus equi is the most common cause. In adult horses, pneumonia can occur following an episode of oesophageal obstruction (‘choke’) where food material and saliva have been accidentally aspirated or following long travel. Journeys of over 6h are a known risk factor for pleuropneumonia, a serious condition where bacterial infection of both the lungs and chest cavity occurs. Horses present with fever, cough, nasal discharge, increased respiratory rate and, with pleuropneumonia, may also show reluctance to move. Diagnosis is via ultrasonography of the chest to identify lung abscesses, collapsed lung lobes and the presence of fluid in the chest cavity. Treatment requires intensive care, intravenous antibiotics with additional drainage of any infected chest fluid present (Fig. 5), and is not always successful.

• Equine Mulitinodular Pulmonary fibrosis

Recently equine herpesvirus 5 has been identified as the cause of a fibrotic lung disease caused equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis (EMPF). Horses present with severe respiratory distress, intermittent fever, cough, nasal discharge, decreased appetite, weight loss, thin body condition and lethargy. This disease is rare but can be identified by PCR and lung biopsy. Some response is reported to antiviral medication but most horses require euthanasia.

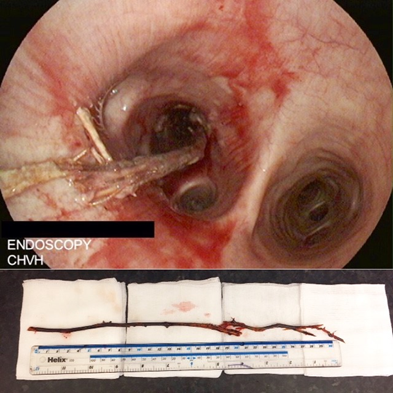

• Foreign body

Inhalation of a foreign body, e.g. a stick, can be a rare cause of a snotty nose (Fig. 6). Usually endoscopic removal can be performed with antibiotic treatment of any secondary bacterial infection.

Figure 5 : Horse with pleuropneumonia (infection of lungs and chest cavity) with a chest drain to allow drainage of purulent fluid from the chest cavity.

Figure 6 : Endoscopic picture (top) of a stick in the right main stem bronchus and below the stick following removal.

• Neoplasia

Neoplasia (cancer) of the lower respiratory tract is a rare cause of purulent nasal discharge. Horses may otherwise be well or may also present with fever and depression. Masses can usually be located by a combination of endoscopy, radiography and ultrasonography. Unfortunately, such disease is not treatable in horses.

• Parasites

The immature larval form of the intestinal roundworm (Parascaris equorum) migrates through the equine lung and is a common cause of snotty noses and ill thrift in weanlings and yearlings. Horses develop natural immunity to this parasite around two years of age. There is now widespread resistance of Parascaris to ivermectin and therefore large burdens can develop on studs that only use this wormer.

The equine lung worm Dictyocaulus arnfieldi can cause a snotty nose and coughing in adult horses. The donkey is the preferred host and it is rare for an infection in horses to result in the development of egg producing adults. Therefore, horses generally require co-grazing with a donkey to become infected. Treatment with ivermectin based wormers is successful.